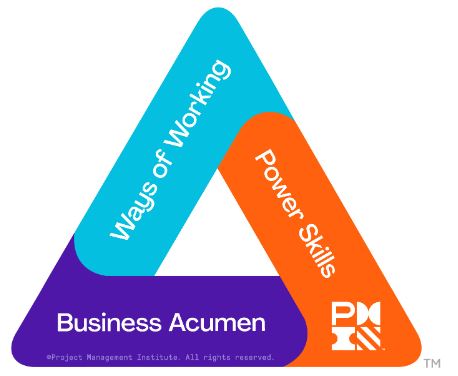

PMI Talent Triangle: Power Skills (Leadership)

Welcome to the PMO Strategies Podcast + Blog, where PMO leaders become IMPACT Drivers! Today, we are talking to one of my favorite people in the entire world, Lee Lambert. Lee and I go way back to my early career as a board member of PMI chapters, around 2004. Lee is one of the founders of the PMP, and a PMI fellow, with over 50 years of experience. That’s right, five zero years of experience. He has held executive level positions and provided management consulting support to companies such as IBM, Motorola, General Electric, Sprint, Roche, and a plethora of government agencies. As an instructor, he has addressed over 50 thousand students in 23 countries, and was named PMI’s professional development provider of the year. Lee is back again this year, to be a part of the 2019 PMO IMPACT Summit. Lee’s session is all about project portfolio management. He’s going to thoroughly examine the methods of realizing the potential value of project portfolio management, and explain why that is the thread that holds management and projects together. He’s going to dive deep into that in his session as a part of the Summit.

Laura Barnard: Today Lee is going to talk a little bit about the whys and the big picture, and how people think about how they should be leveraging project portfolio management, what’s available to them, and what opportunities we might be missing. Lee Lambert: That’s correct. I really want to talk a little bit about the power of the process and then maybe what’s available in the process. I’ll use an example of a small company some of you are probably familiar with, IBM.

Lee: When I had an opportunity to go work with IBM in 1993, this is when they were in … They were struggling. They were projecting an eight billion dollar loss that year. That’s when they brought in Lou Gerstner. Lou Gerstner had an interesting background, credit cards and tobacco, so how he was qualified for IBM, I learned later was because he thinks holistically. He came in and immediately put out a, well we’ll call it an edict, that project management was going to be implemented and it’s going to become the thread that held the entire organization together.

What he found was that there were far too many projects being planned and scheduled and approved, far more than they had people to execute them, far more than they had the time to get through them. He eliminated hundreds, literally hundreds of projects, and to focus on those that were going to deliver the most value for the organization. It took about three years for people to realize he wasn’t kidding, and really begin to focus. They established a center that we now refer to as a PMO, but they called it the Project Management Center of Excellence. They controlled the information development and training. At the end of three years, they had a very tightly integrated system. If they wanted to look at manpower loadings across time, if they wanted to look at where their costs were divided, where they were spending their money, all of that was available upon request. The value of the enterprise application is that if somebody decides that they need a certain kind of information to support their decisions, they can get it; it’s there. It’s in the system and it’s available to get there. The standardized reports are dangerous, because you can end up with way more information than you need, information that doesn’t really support the system that you’re going to be using. IBM was the leader in this area. If you watched any of the stuff that Laura does, I met her when she was just a child. She was seven or eight years old. If you look at what she’s doing with her organization, she’s really highlighting what it is we’ve been trying to convince people of for years, is that the information to support the decisions is there. All you have to do is figure out how you want to get it out. Now, we’re seeing much more interest in that. We’re seeing organizations focused on enterprise systems. We’re seeing organizations focused on enterprise systems. If you look at any of the big vendors, they’ve all got their enterprise applications.

Laura: There’s just so much in all of that. I’m thinking about the former me that spent 15 years inside organization as a PMO leader, and I remember and can reflect on where a lot of our PMO leaders listening today, are. What I’m always telling them is, “Listen, you are there to provide information for executives to make educated and informed decisions, so that you can move projects forward, you can make sure that the return on investment is achieved for the strategic initiatives that are undertaken, and that you’re focusing on the right things in the first place.” You brought up a good point though, that back in the day there really wasn’t the ease of getting access to the information. Now, see a lot of people in positions where they feel like more information is better, so they just start flooding with every possible metric that they can gather, and they start flooding their reports, and overwhelming their stakeholders and executives with so much information. How do we have the right mindset, the right approach, before we even dig into taking advantage of what we already have in front of us? How do we even have the right mindset about what information is necessary, and how would you recommend PMO leaders are thinking about their role in driving those decisions?

Lee: That’s a good question. The problem with what information do I need, is really going to be driven by the executives and the PMO working together to determine what information will support your decision making. There’s a little bit of trial and error in that. There’s not always going to be the best information for the specific need, so we have to retool that just a little bit. If you got to a vendor and say, “I want enterprise project management,” they say, “Well, here. We got it right here for you. Go ahead and take it.” That isn’t going to work. You hear it’s off the shelf until you spend three million dollars modifying it. You’ve got to look at it in that way, “How do we get it?” Well, we have to take the time to sit down and talk about what kinds of information you need. One of the things in today’s matrix environment that is critical, is resource information, resource distribution, because we’ve got this idea that we have these pools of skillset confident people, and we’re just going to assign them to projects. If we do that independently, poor little Bob is assigned to five projects at the same time, and all of them are critical projects. People will rise to the occasion, but eventually they become overloaded and that effect is negative. With an enterprise approach, I take all those project plans. We’re starting at the base. You don’t start at the top; you start at the base with all the projects. Then you integrate all that project information. If I just take the resource issue, and I begin to integrate those resource distribution data, and I find out that as soon as Bob’s over-committed, I get a little signal that says, “You’ve got a problem here. Then I can resolve it. The key here is, that information is till there even if you aren’t using it. If somebody needs a certain piece of information, you can pull it out, but why would you send that to everybody all the time? What we need to do, and how many times have you heard management say, “There’s just too much information. I can’t sort through all this.”? What we’re trying to do with the enterprise approach, in my view, is to create the ability to have all the information, if that’s what you need. We also have the ability to have two pages, if that’s all you need. We’ve got to understand that we’re going to create a process where there’s more information in there, than any one individual, whatever really have the need for, and if they do, they can get it. That’s a struggle, because that takes time and it takes coordination. It takes integration. Integrating these systems is not like it used to be, for sure, but it still takes a lot of attention, and in a way, cost.

Laura Barnard: It’s so funny. We get so caught up in creating our outputs, that we forget to focus on the outcome, which is that this information is being used to drive educated and informed decisions, to move people faster to their decision making process. If you’re going to put so much information in front of them, you create what I like to refer to as information indigestion, right? They’ve got to much information in front of them, they can’t digest it mentally. Therefore, they are frozen. Executives can’t make decisions, projects get stuck. It’s hard enough to get on their calendars anyway. You go into a meeting and you find that they’re down on the bottom of page 16 of that 24 page report, and they’re stuck on some data point. Then you end up spending the whole meeting on that one data point, and you’re thinking to yourself, “This wasn’t even relevant to the decision I needed,” then I say, “Hey, PMO leaders and project managers, you put in front of them,” right? If we’re not focused, and these days, people don’t have the attention spans they had back when you were starting out. People will just, if they can’t see it on one page, it seems like, or in the top half of their phone when the email comes, they’re not even paying attention to it. They’re just scrolling past it, moving on, getting distracted with other things. I feel like whatever we can do to get them laser focused specifically on the issue that we’re trying to get them to address and move them through that faster, the better off we’re going to be. I think you’re really hitting an important point that you don’t have to boil the ocean to start making progress with PPM. You can just start with one pot on the stove at a time. You can just start with resource management.

Lee: I think they just have to sort through what they already have. If you think about it, let’s stay with the resource thing for a minute. If you think about it, almost every project manager does resource planning. That’s part of the planning process. Well, all we’ve got to do now is look at how do we capture with clarity, what the resource loads are across my project, and then compare what the loads for those individuals are on another project? If nothing else, project managers ought to think about it in a way that this gives me validated, and I’ll use the word “excuse,” why our project’s in the position it’s in. I can validate it with the information that results from our project management system. Then let’s focus on each project.

Laura: Right. That makes perfect sense. PMO leaders listening might be like, “Okay, that’s great, but I can’t get any budget for this,” or, “I can’t convince my executives that this is going to be useful,” or they might even hear or know, even if they’re not hearing it, that people don’t, like in all of the teams, all their stakeholders don’t want transparency, because they don’t want their pet project to get pulled or the light to be shined on how they’re doing things in their area. How would PMO leaders in that position, where they can’t even convince people that this is important, what advice do you have for them on how to get that support needed, to even put the basics of PPM in place?

Lee: That’s an interesting question. One thing it takes is time. I think people need to realize that there’s no quick fix. If you look at that, I’m going to say a really awful word that most project managers don’t want to talk about, closeout. I’ll tell you what. If I can’t sell the value of it, the only other way I can illustrate the value is to take a project that had a problem and define how better information sooner could have helped avoid that problem. Usually, there’s a cost associated with it. In other words, use lessons learned as your message. I can tell you, IT people, the CIO he’ll come in and tell you that he wants to buy an off the shelf package that’ll save the company 10 million dollars a year. Where did he get those numbers? He doesn’t know that. Management and decision makers go, “Well, how do you validate that?” Instead of trying that approach, take projects that had difficulties, had challenges. Define those challenges and then define what could have been done with better support information sooner. If you can’t find that, you’ve got a problem. If you can’t find where the enterprise information might not have really made any difference, well then don’t use that as a selling point. You’ve got to take a project that’s had a problem, and frankly, the more visible the better, and can figure a methodology that would have said, “If we would have been able to do this project much more effectively.” That might get their attention.

Laura: That’s something that my IMPACT Engine PMO course, which is a soup to nuts, start to finish, “Here, whether you are trying to hit the reset button on your PMO or building it from scratch, the steps that you need to go through,” and it really closely follows my consulting framework that I’ve used to help PMO leaders all over the place, build and run a PMO and implement project management capability. One of the things that I always talk about it in there, one of the things that I talk about in my courses, like making a case for PMO, all of them, it all starts with identifying the pain, right?

Laura: If you want to move the organization forward, you have to get crystal clear on why, why for everything. Why the PMO? Why is the PMO a solution? Why is the service that you want to put in place the right service? All of it goes back to who’s problems are you solving? If you want to get stakeholder buy-in, if you want people to engage, if you want funding, support, any of it, you’ve got to be able to say, “This is the pain I’m going to fix for you,” right? I think it’s perfect to say, “Look at the lessons learned. Look at the failures. Look at where people are experiencing pain,” and even talk to the people that are being overwhelmed on the projects. This all shines a light on the fact that with this PPM thing, and can be a solution to so many root cause problems that you’re having in your organization. It’s a huge opportunity for PMO leaders to look at and look for those root causes, and find ways to address some of that pain. Even if people don’t realize it, if things just start running more smoothly, you will be their hero. That’s the kind of hero that you want to be. What are some examples, of some other ways to have an easy, first step along the path of portfolio management? What are some things that they could start looking for, or things that they could start measuring? I always say, “Just start with a few basic metrics, or a few things that you’re going to highlight or provide transparency on.” What are some easy, low hanging fruit ways to do that?

Lee: Well, the first two, I’d always do resources. The second one is I would do cost comparisons, budget versus actual cost. Got to be a little careful about the delay in looking for the actual cost. I understand that’s a very good way to determine something’s going on differently than what we planned. We planned X amount and it’s Y amount is how much we spent. I can do that, and I can do that pretty easily, which means integration with the cost system; it means timely information. I can do that very quickly. The other big thing though, even if I take the low hanging fruit and think about it, and I roll that information up, then the decision makers have to be willing to make a decision. Nothing more frustrating than working to integrate all of this information, and really getting excited. I know project managers don’t get that excited, but really getting excited about what you’ve provided to the decision maker, and then the decision maker goes in a different direction or doesn’t even use it at all.

Laura: That’s why I really like how you’re talking about top down and bottom up, kind of both, right? You do the bottom up with how you gather all of the data to give that bigger picture perspective, but you also mentioned having conversations with the executives about what they actually need. I always say that if you assume, you’re probably wrong. Never think that you have the answer as to the medicine that they need to take, because they’re not going to take it. The only way you’re going to get them to take the medicine they need to take, is if it comes from them first, if it’s their idea. You might know that there’s five data points, that if they had them they would be able to make better decisions. If that’s not the data they’re saying that they need, then you’ve got to start with what they need first. If you tie those data points they’ve asked for to the pain that it’s going to solve, usually you can get them to actually use that information. If you’re just coming to them with, “Look at my fancy report. Look at my great stuff. Look at how wonderful I am with all this data I’m giving you,” they’re not going to care.

Lee: Yeah. I agree with that. The problem is, it’s like that doctor when they try to give you medicine. You don’t want to take it because you think it’s poison. That’s what we run into. We do that with our kids all the time. “No, take this. It tastes good,” and it tastes like crap. What happens is the trust level goes down. Somehow, we’ve got to convince them, “No, it’s not poison. It’s good stuff. It’s the medicine you need to get well.” Once that light goes on, it almost becomes negative, because now they begin to ask for too much information. You also have to be the filter to question. “Are you sure you really need this?” We have a dual role where, “Oh, we want to provide you all this information. Oh, but not that. We don’t want to provide you that.” There’s a personality issue, there’s the ability to communicate effectively with senior level people, so they understand you’re not just trying to build a PMO empire, that you’re actually trying to help the organization be more profitable. Once you do that, once you get their trust, then it goes a lot more smoothly.

Laura: And the way you get that trust is by solving a problem for them, right? I always say that there’s some rules that PMO leaders need to have in their organization, and one is a fiduciary, right? Every one of those projects that they are managing, or overseeing, or are responsible for, should be yielding the highest possible return on investment, and that’s what those projects are, is investments. Also, they are the strategy navigator, helping to make sure that those projects are seen to all the way to completion, but most importantly they’re a trusted advisor. You have to build that trust slowly. By building that trust, you can … They’ll have the right conversations with you about what they need, and they’ll listen when you say, “Well, you don’t need that as much as you need this,” and, “Are you sure you need that?” et cetera. I can see it going down that rabbit hole of, “Okay, now we’ve got 50 metrics that we want to gather,” and that’s not really what they’re using to make decisions. When you start getting into that rabbit hole with your executives where, “Great! Now you gave us this information. What about these other 50 data points?” I always like to show them the cost of gathering that information. If it costs a lot of money to gather this information, and time, and energy, and effort, and the more data you’re gathering, the longer it will take. It’ll slow down decision making. I like to get them to focus on their top priorities, and when they start asking for more, say, “Is it worth the investment of time it will take to get this data point, and how exactly is this data point driving decisions?”

Lee: I think that approach is good. One of the things I caution people on though, with that, because often times cost is usually an excuse to not do it, is that the short term long term effects. Maybe it’s going to cost X amount upfront, and that looks like a lot of money for that decision point, but as you use it over time, now it’s free. The next nine months is free. You’ve already implemented, you’ve already put it into place, you’ve already absorbed that cost. We really have to make sure they understand this is a strategic decision, and it needs to be thought about as a strategic decision. Not a short term, but a strategic long term decision.

Laura: Right. Well, I think we have given them a good sense of what they can expect in your summit presentation on PPM. Are there any other bits of advice or wisdom from your 50 plus years in the project management space, that you think PMO leaders should keep in mind as they’re thinking about embarking on the journey of either improving, or implementing for the first time, a project portfolio management solution in their organization?

Lee: Yeah. I can sum that role up pretty easily. They have to be cautious, extremely cautious, that they don’t take from being a support organization, because that’s what they are, support organization, and through a desire to control things more, become a gestapo. There’s just no way that it’s going to be effective if they’re seen as the policing organization. They’re the organization providing the information, working with the troops to get the information they need. This is where I get a little hung up on forms and formats. I’ve seen PMOs become template producers. They get a reputation for that. I tell that joke all the time in my classes. It gets a great response. The fact of the matter is, they convert from support to gestapo. It gives them power. It gives them a sense of strength. They got to give it up. You’ve got to be a service organization. If you’re not, it won’t be effective. People will … It’ll look like they’re supporting you. They’ll be careful to make it look like they’re supporting you, but they’re not giving you what they need to give you to be effective.

Laura: Right. That’s so important because information is power. If we use that for evil instead of for good we’ll end up in a really vicious situation. Lee, it’s been an honor as always, to highlight you and just have a great conversation with you. I am honored to be a part of your network and I’m grateful for everything that you’ve done for the project management community, for PMI, and for my IMPACT Driver community specifically. Thank you so much for being here today.

Lee: My pleasure. I always enjoy working with you, Laura. I can tell by the smile, that you actually enjoy what you’re doing. That’s a key.

T hanks for taking the time to check out the podcast!

hanks for taking the time to check out the podcast!

I welcome your feedback and insights!

I’d love to know what you think and if you love it, please leave a rating and review in your favorite podcast player. Please leave a comment below to share your thoughts. See you online!

Warmly,

Laura Barnard

Great and an informative article!

King regards,

Boswell Henneberg